The reading captured from China marks a first for this kind of radar technology

Scientists using a radar in China have managed to detect strange ‘bubbles’ over the pyramids all the way over in Egypt.

The huge structures have always been a source of mystery for us, from the questions and theories about how they got built in the first place to what they conceal inside.

Now, that mystery has extended to the air above the pyramids as the researchers from the Chinese Academy of Sciences have recently shared their findings.

The mysterious bubbles were detected over the pyramids (Mohamed Elshahed/Anadolu via Getty Images)

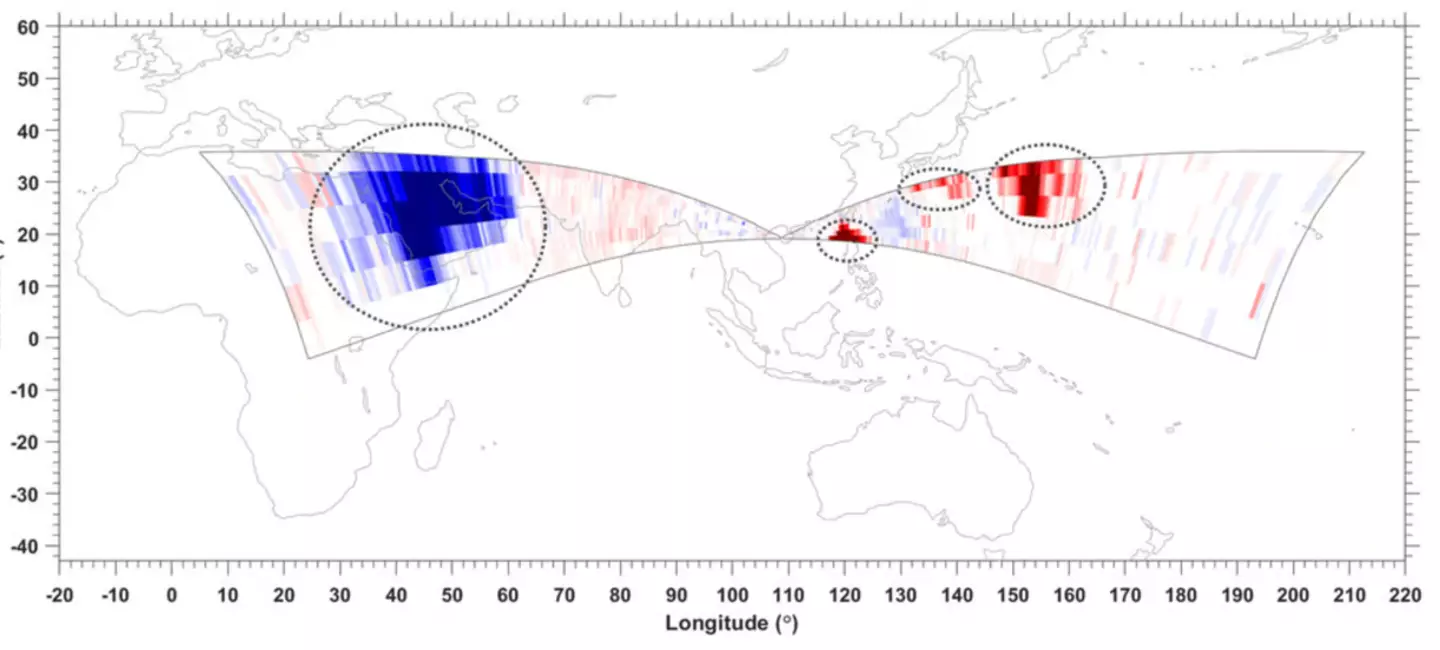

Using the LARID radar, a low-latitude long-range ionospheric radar, the scientists detected what are known as equatorial plasma bubbles (EPBs) over the pyramids.

These bubbles exist in the higher atmosphere, and are made up of hot pockets of gas which form at low latitudes.

In early November 2023, a solar storm caused the plasma bubbles which showed up on China’s radar from as far as North Africa and the central Pacific.

The readings allowed scientists to track the movements of the bubbles in real-time.

They can grow hundreds of kilometers wide, and while they are not uncommon, scientists don’t know much about them or about their ability to disrupt GPS signals and interfere with satellite communications.

EPBs are typically observed from space so researchers are able to get a global view of them. They can be observed from the ground, but the curvature of the ground radar can make it difficult for it to pick up readings below the horizon.

The radar bounces off the ionosphere (Chinese Academy of Sciences)

What makes this observation of EPBs particularly noteworthy then, is the fact it came from 4,970 miles away.

China’s radar can monitor the irregularities which are caused by plasma bubbles by interpreting the signals it receives from the radar reflected against the plasma of the ionosphere.

Its reading from Egypt makes China the first country in the world able to detect EPBs on radar.

The radar is able to detect signals from 5,965 miles, and the researchers have suggested that creating a network of similar radars could be game-changing when it comes to monitoring these events.

Sharing their findings in a paper published in Geophysical Research Letters, the authors wrote: “The results provide meaningful insight for building a low latitude OTH [Over-The-Horizon] radar network in future, that consists of three to four OTH radars [and] could have the capability to obtain global EPBs in real time.”

By tracking EPBs, scientists could gain the ability to forecast their location, size and timing, potentially reducing the disruptions they can cause to satellites.