The ‘Well-man’ was discovered in 1938 and now, researchers know what happened to him

Researchers have finally figured out the identity of an 800-year-old skeleton which was found in a well.

Known as ‘Well-man’, it was discovered at Norway’s Sverresborg castle and was even mentioned in a passage in Norse text.

Sverris saga talks about the real-life King Sverre Sigurdsson, and also a moment where a dead man was tossed into a week during a military raid in 1197.

According to the text, raiders threw the body into the well to poison the main water source, but nothing more identifiable about the man was included in the passage.

Because of this, researchers were able to pinpoint when the man was placed in the well, and why.

It was in 1938 that the body was initially discovered, however due to a lack of resources, they could only look at him and excavate a few bones.

But now, scientists have been able to figure out what he would have looked like thanks to technological innovation.

A new study, which was published on Friday (October 25) in the Cell Press journal iScience, revealed its in-depth research through samples of his teeth.

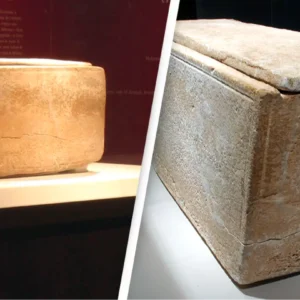

The ‘Well-man’ remained a mystery for years (Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research)

A breakthrough discovery

“This is the first time that a person described in these historical texts has actually been found,” said study co-author Michael D. Martin, a professor at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology’s University Museum in Trondheim.

He added: “There are a lot of these medieval and ancient remains all around Europe, and they’re increasingly being studied using genomic methods.”

The findings figured out the surprising reason he ended up in the Norse saga too.

The Sverris saga was the period from the rise of King Sverre, who was born in 1152 and died in 1202.

He reigned over Norway during the second half of the 12th century after a succession battle with his uncle.

Many have speculated that someone close to the King wrote the text as it was happening, and gave details such as full names, locations, battles and military strategies.

The crucial moment occurred in 1197, as King Sverre spent the winter in Bergen.

His enemies carried out a surprise attack hundreds of miles away against the Sverresborg castle and burned everything inside.

In a line in the text, they mention the dead man: “They took a dead man and cast him into the well, and then filled it up with stones.”

Thanks to his teeth, researchers were about to work out what he would have looked like (Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research)

In 2014 and 2016, the well was once again excavated and more of his remains were taken away for testing, including his skull which was separate from his body.

Researchers suggested the man was between 30 to 40 years old at the time of his death.

However, they aren’t too sure of how he died.

They did note that there was a blunt force injury to the back left part of the skull, as well as two sharp cuts, but they believe this happened before he died.

What did the Well-man look like?

Lead study author Dr Martin Ellegaard, of the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, used samples of a tooth to find out that he had a medium skin tone, blue eyes, and blond or light-brown colored hair.

“The biggest surprise for all of us was that the Well-man did not come from the local population, but rather that his ancestry traces back to a specific region in southern Norway. That suggests the sieging army threw one of their own dead into the well,” Dr Ellegaard said.

He added: “However, showing that his genetic origin may have been in southern rather than central Norway, as was originally expected, changes our perception of the circumstances surrounding the decision of the victors to deposit this particular human carcass in the well. It opens up new possibilities for interpretation (for why the body was dumped) and allows for a deeper understanding and novel insights into stories we thought were largely understood.”

Dr Ellegaard noted: “Archaeological science, ancient DNA and genetic analyses give us tools to separate fact from fiction, which eventually should give us a more objective and complete view of human history.”