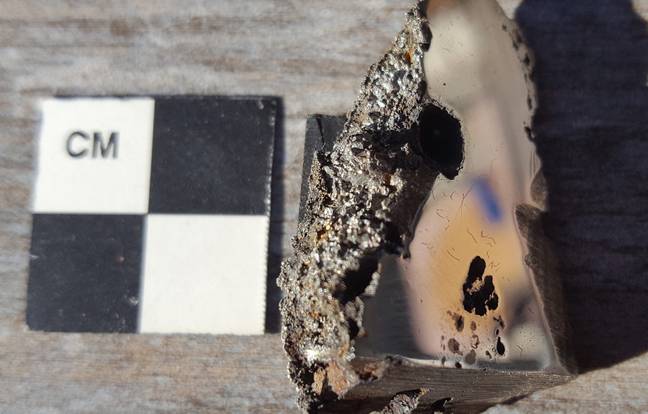

A research team has discovered at least two minerals they’ve never seen on Earth before inside a 15-tonne meteorite found in Somalia.

The University of Alberta analysed a slice of the meteorite – which fell in 2020 -and discovered two, if not even three minerals, that have never before been seen on our planet.

That information alone is pretty darn impressive but it turns out the team also identified the meteorite as the ninth largest in the world.

Chris Herd, Professor in the Department of Earth & Atmospheric Sciences and Curator of the University of Alberta’s Meteorite Collection, said: “Whenever you find a new mineral, it means that the actual geological conditions, the chemistry of the rock, was different than what’s been found before.

“That’s what makes this exciting: In this particular meteorite you have two officially described minerals that are new to science.”

Dr Herd revealed that while he was classifying the rock, he discovered some unusual minerals and asked the head of the university’s electron microprobe laboratory, Andrew Locock, to observe it.

“The very first day he did some analyses, he said, ‘You’ve got at least two new minerals in there’,” said Dr Herd. “That was phenomenal. Most of the time it takes a lot more work than that to say there’s a new mineral.”

If you’re wondering what to call these two babies, they have been named elaliite and elkinstantonite, which don’t exactly roll off the tongue that easy.

However, there’s a reason behind these interesting names.

The first mineral is named after the meteorite itself, called ‘El Ali’, as it was discovered in the town of El Ali, which lies in the Hiiraan region of Somalia.

Herd revealed he named the second after Lindy Elkins-Tanton, vice president of the ASU Interplanetary Initiative, professor at Arizona State University’s School of Earth and Space Exploration and principal investigator of NASA’s upcoming Psyche mission.

He said he wanted to name the mineral as a tribute to the professor’s ongoing work with planetary core elements.

Dr Herd explained: “Lindy has done a lot of work on how the cores of planets form, how these iron nickel cores form, and the closest analogue we have are iron meteorites.

“So it made sense to name a mineral after her and recognise her contributions to science.”

He added of the discovery: “Whenever there’s a new material that’s known, material scientists are interested too because of the potential uses in a wide range of things in society.”

While Dr Herd would like to continue investigating the meteorite, it’s being relocated to China in search of a potential buyer.

According to The Guardian, meteorites are often bought and purchased on international markets.